As a teenager in Tallahassee, Florida, I haunted Florida State University's Strozier Library, a godsend for its titanic air-conditioned chill and its city of books. Among its endless shelves were what passed for a good comics and cartooning section, circa 1978, forbidding rows of bound volumes of magazines, and, in its basement, fat stacks of cardboard-boxed microfilms.

|

| Strozier Library, Florida State University, 1970s |

Amidst collegiates who muddled through statistics papers and other chores of higher education, I wandered through the seven decades of newspaper comics available to me. Most of the newspapers on file were Florida-based, but the stacks also included The Chicago Tribune, several California dailies, Southeast, Midwest and Southwest papers, Afro-American papers, and territorial, pre-statehood Alaska editions.

|

| Microfilm reel, c. 1978 (pencil sold separately) |

I couldn't obtain these strips; I could only view them in the dark, squeak-squeak-squeaking the stubborn turnstile on the side of the viewer. The microfilm department had a printer, but the results were dreadful, given that the source material was sub-par and the clay-like, smelly mimeograph paper a poorer host.

That the comics survived, even in this debased, often distorted form, was a small miracle. The contempt shown for comics by libraries was made clear in these spools of muddy microfilm. If the Sunday edition of a paper was included, chances were everything BUT the comics section would be there. Stubborn, biased microfilmers included ad circulars, TV sections, women's magazines--none of which could have any research value, unless a person needed to know the price of hair spray in 1948, or get an ancient recipe. It felt like a spiteful act to those of us whose only reason for bothering with this ritual WAS the comics.

This experience can be had, in the comfort of your home, via the Google News Archive. Google has suspended this effort, and many of its selections are pre-comics papers, or desolate rural weeklies barren of any comics content. The excision of Sunday comics in those papers that DID run them is maddening, just as it was in the mid-to-late 1970s.

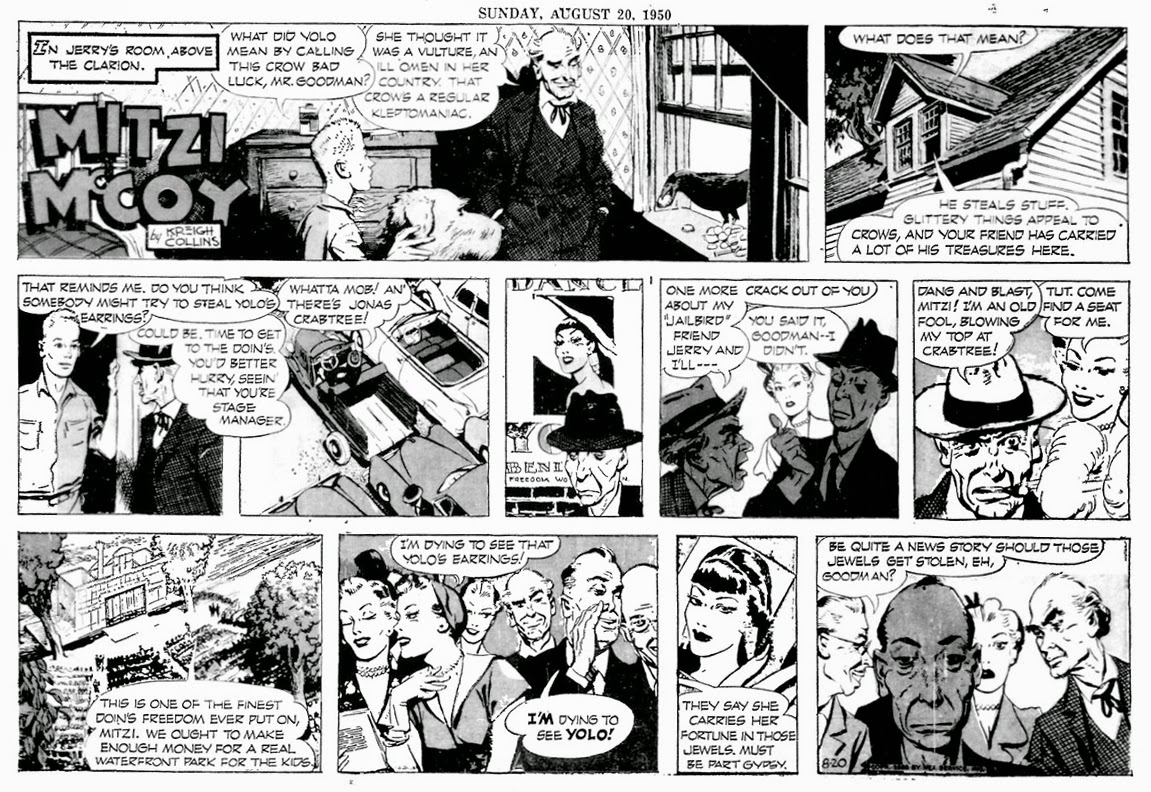

I recently revisited this ur-world to answer a minor question about a comic strip that abruptly changed course twice in a run of almost 30 years.

Its artist has remained a favorite of mine, for his nimble, vigorous style--a look and feel that suggests a marriage of Will Eisner and Bernard Krigstein, garnished with a touch of old-school book illustration. Kreigh Collins never worked in comic books, to my knowledge. He was a book illustrator and a painter, earlier in life, until an injury forced him to abandon canvas for several years.

Here's an excerpt from a biographical sketch I found online:

Kreigh T. (Taylor) Collins majored in art at Cincinnati (Ohio) High School. He also studied art in Cleveland (1924-1925), and in 1925 opened his own studio. He met Theresa VanderLaan, whom he married in 1929 after a year spent studying in Paris (with visits to North Africa). She became the model for characters in “Up Anchor” and “Kevin the Bold,” as well as model for many of his sketches and paintings. They moved to Chicago in 1929, where he made illustrations for an advertising agency. In the fall of 1930 the Collins family moved to Grand Rapids, Michigan, where he again took up advertising illustration. In 1931, he and Theresa returned to Paris where he studied and first began to concentrate on landscape painting.

|

| Kreigh Collins, self portrait, c. 1928 |

They returned to the United States in the midst of the Depression, but Collins did well by selling landscapes he painted while living in the small village of Leland, Michigan. He also contracted with a newspaper syndicate to illustrate the “Do You Know” series by Willis Atwell for the Michigan Centennial. He painted portraits in Ohio, eight murals in Dallas, Texas, and landscapes in Taos, New Mexico. All this work caught up with him and by 1937 he could no longer use his right arm to paint. He discovered that he could make line drawings by resting his elbow on the arm rest of a chair with his forearm on a drawing board. The Methodist Publishing House, which had until then bought only a few of his travel sketches, started sending him large quantities of work. He also illustrated the Informative Classroom “Teaching Pictures.” In 1941 he found he could do a small amount of painting again without pain and it was then that he must have worked on book illustrations for the John C. Winston Company of Philadelphia.

Collins illustrated several other books in the earlier 1940s, and continued this during his comic strip career. Many of these books are high-priced collector's items, and can be glimpsed on amazon, if you're so inclined. I recall seeing some of these books during my lone visit to Bill Blackbeard's staggering comics archives in 1992. My notice of, and interest in, those Collins-illustrated books assured Blackbeard that I had some grounding in comics history; the tone of our visit brightened notably after that moment.

|

| Book jacket illustrated by Collins |

"Mitzi" seemed designed to appeal to a bigger market. Among its debut papers was the Pittsburgh Press, which accorded it much ballyhoo:

Of course, whomever microfilmed the Press disposed of its Sunday comics sections. What does exist, via other papers, suggests a potential not reached, and a genuinely appealing post-war comic strip idea. Mitzi was an attempt at a sort of Frank Capra movie in comics form.

Another Pennsylvania paper, the Reading Eagle, ran the strip, and its sequels, into the 1960s. This is the first episode I could find in Google News, dated 11/7/1948. It feels like a first episode, but the Pittsburgh Press' squibs date from one month earlier. Anyhow, here it is:

This strip seemingly introduces the "picturesque little town of Freedom," and its three main characters--Stub Goodman, gently cantankerous liberal small-town newspaper editor, Tim Graham, his Jimmy Stewart-esque reporter/sidekick, and Ms. McCoy, a vivacious, outspoken child of moolah (and blond bombshell). These major characters, plus a plethora of townsfolk, including cranks, crackpots and "just folks" were a potentially compelling and adaptable cast of characters. Collins' gentle, often moody artwork seems a fine visual vessel for this material. It could have been a counterpart to the quiet mood of Frank King's Gasoline Alley, as well.

The strip also has tacit corollaries to Eisner's Sunday-only Spirit. From its Abe Kanegson-ish lettering (done by cartoonist Art Sansom) to its simulacra of the Commissioner Dolan/Ellen Dolan/Denny Colt relationship, minus masks, gloves or fisticuffs, these similarities must have been sheer coincidence. There are a few action sequences in Mitzi, but its events are mostly hands-in-pockets, leaning-on-the-fence chit-chat between friends and neighbors.

Mitzi McCoy never really got a chance to develop. Its Sunday-only half-page continuity results in elided, rather rushed storytelling, in which possibly good ideas are telegraphed, never thought out, and dependent on the artwork to carry them across the finish line. It wasn't the first newspaper comic strip to waste a potentially solid concept--nor was it the last.

Despite the distaste of the Press' microfilmers, the paper obviously thought well of the strip. The Reading Eagle, which had one of the best Sunday comics sections of its time, is incomplete on Google News. The first several months of McCoy are spotty. To make the hunt more fun, the microfilm photographers opted to bunch several days' editions together. Thus, the Sunday paper has no comics; those are in the middle of a file that might contain Thursday through Saturday. The Eagle's Sunday comics section is there, if you're willing to kill some time digging.

Weeks and months are missing, here and there, so reading a complete run of this strip (or many others) via Google News is impossible.

Though the microfilms have deteriorated (a plight eloquently described by Nicholson Baker in his controversial book Double Fold: Libraries and the Assault on Paper), reducing fine linework to inchoate blobs, I was able to capture and touch up the strip's final sequence, which is notable for its out-of-left-field turn.

I've never seen an episode of Mitzi in newsprint form. Clippings almost never turn up for sale, and it's unlikely (but possible) that a complete run exists in printed form. Here's the opening panel of the 8/26/49 strip, from a long-ago eBay sale:

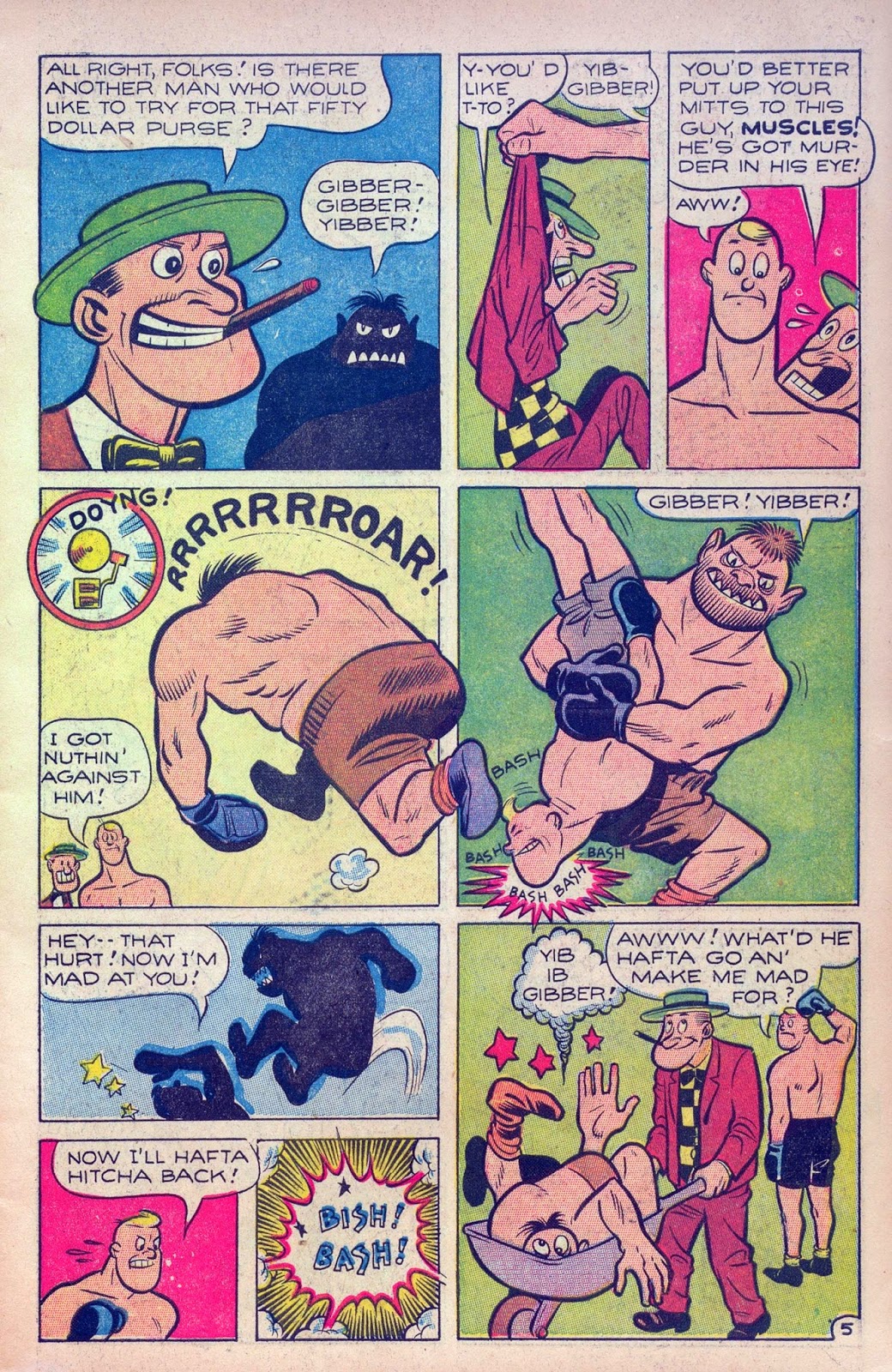

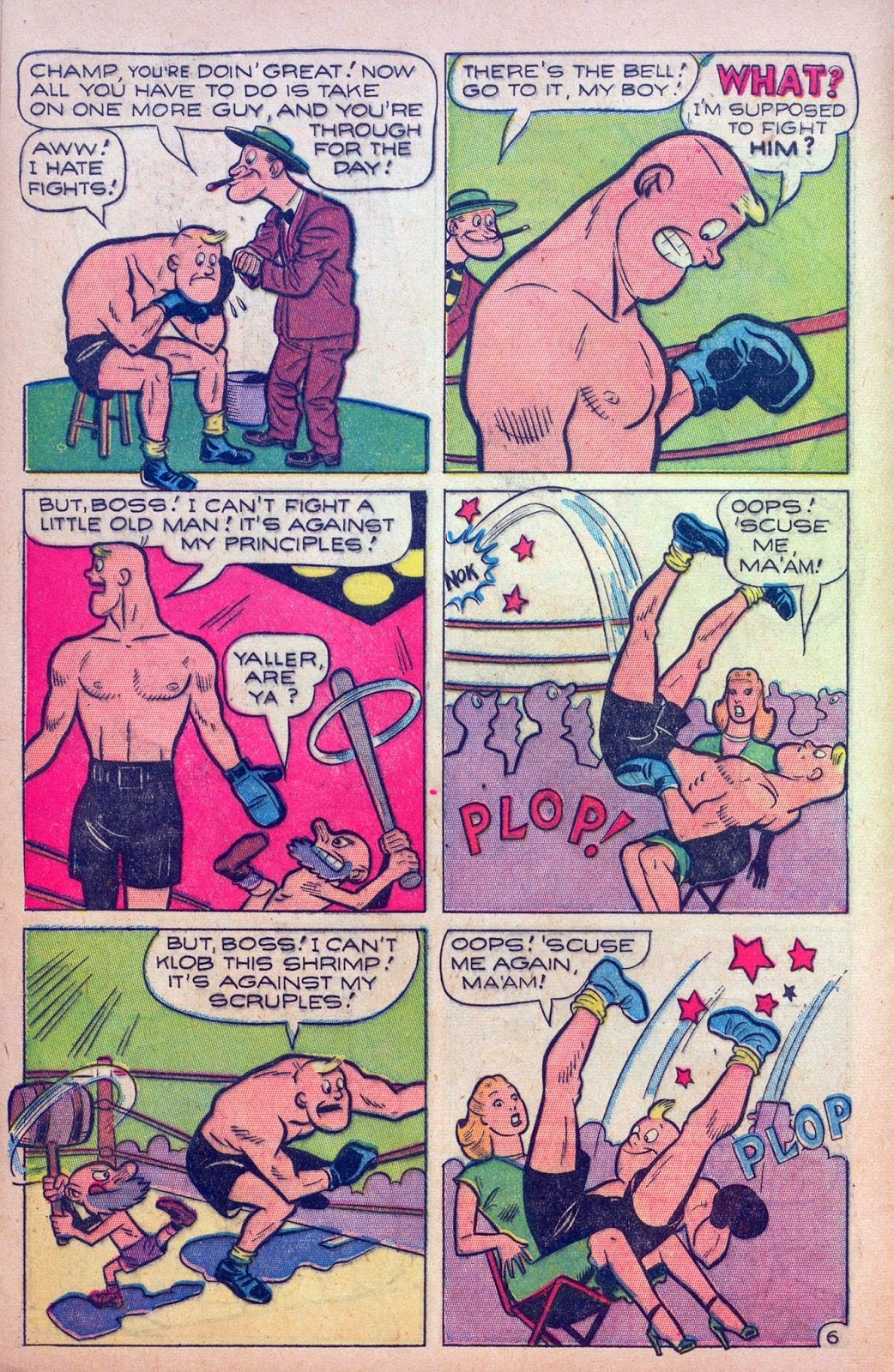

The following sequence offers a blurry but readable taster of Mitzi McCoy. I've done my best to balance and enhance these decayed images.

I don't believe Kreigh Collins wrote "Mitzi." The author may have been Russ Winterbotham, a SF writer who handled many NEA continuities in the later 1940s and 1950s. The anonymous trudge of the dialogue, which often seems at disconnect with Collins' charming, caricatural illustrations, sucks the life out of the events in this sequence.

Collins works to consciously imbue these talking heads with presence and life. His atmospheric efforts of the last two strips, above, though marred by time and poor reproduction, show an ambition to go beyond the typical look-and-feel of the post-war continuity strip.

None of Mitzi's readership could have anticipated that its next episode was its last:

There was a precedent for this tale-telling scenario. A two-part series detailing the history of the Irish wolfhound apparently made a hit with readers and editors in July, 1949. Here's part one:

Stub Goodman spun a birth-of-Christ yarn in the strip's December, 1949 sequences. Here are the first and last installments of this detour. Note Collins' self-reference in the first strip, plus Stub Goodman's preaching the gospel of comics in the next-to-last panel:

The sequence showed Collins' affinity for historical drama--an outlet not otherwise found in a contemporary strip about small-town America. In a reverse of V. T. Hamlin's career, in which his stone-age Alley Oop became a history-spanning time traveler, Collins and his writer(s) took the strip back 400 years, without so much as a fare thee well to the readers of modern-day Mitzi,

Mark II of the strip was called Kevin the Bold, and it was picked up by the Chicago Tribune from its debut episode, seen here in Murk-vision, but with a "Mitzi McCoy" logo:

Mark II of the strip was called Kevin the Bold, and it was picked up by the Chicago Tribune from its debut episode, seen here in Murk-vision, but with a "Mitzi McCoy" logo:

As Kevin the Bold, the strip enjoyed a precipitous jump in circulation. NEA, like King Features and other earlier syndicates, offered a pre-print Sunday comics section for small-town papers too low-budget (or lazy) to bother with such things as editorial selection and four-color printing. Kevin was often the lead feature of the NEA ready-made. An earthy alternative to the restrained Prince Valiant, it was often picked up by choosier papers who couldn't afford Hal Foster's strip, or published in an area where Val was already claimed.

The NEA pre-made sections were shoddily printed--slightly better than the average comic book of the 1950s. The Chicago Tribune's version was lovingly handled by the paper's journeymen engravers, with often-stunning results. Here's a Tribune-ized version of the 7/8/1951 episode, from my collection of about 100 clippings:

Collins took over authorship of Kevin in the mid-1950s. It continued into late 1968. The Chicago Tribune ran it until at least 1958. Thanks to NEA's captive audience market, it appeared to the end of its existence in many newspapers. After other NEA adventure strips (Chris Welkin Planeteer, drawn in sub-Caniff style by Art Sansom, and private-eye Vic Flint) bit the dust, Kevin soldiered on.

Almost 20 years after its first morphing, Kevin underwent another literal sea-change. Here is the final episode of the strip, plus the first two of its new identity as Up Anchor!

The NEA pre-made sections were shoddily printed--slightly better than the average comic book of the 1950s. The Chicago Tribune's version was lovingly handled by the paper's journeymen engravers, with often-stunning results. Here's a Tribune-ized version of the 7/8/1951 episode, from my collection of about 100 clippings:

Collins took over authorship of Kevin in the mid-1950s. It continued into late 1968. The Chicago Tribune ran it until at least 1958. Thanks to NEA's captive audience market, it appeared to the end of its existence in many newspapers. After other NEA adventure strips (Chris Welkin Planeteer, drawn in sub-Caniff style by Art Sansom, and private-eye Vic Flint) bit the dust, Kevin soldiered on.

Almost 20 years after its first morphing, Kevin underwent another literal sea-change. Here is the final episode of the strip, plus the first two of its new identity as Up Anchor!

Up Anchor! ran until 1973, when Collins retired from cartooning. The strip was semi-autobiographical. Collins and his family were avid sailors, and their adventures (and misadventures) on the water offered local color in newspapers desperate for such things.

|

| Miami News, 6/12/1954 |

|

| St. Petersburg Independent, 11/9/1959 |

.jpg)