Comics are hard work. From writing to penciling to inking, it's a long haul, and often a solitary slog. No matter how savvy an artist or writer may be, the inescapable task remains. A blank page must be filled with words and images. The words take much thought to write; the images take much longer to design, sketch and render. If those images are to be printed in color, the artist (or another talented person) has to choose and apply the colors. That, too, requires much time and thought.

Comics-making can be joyless work--although the endgoal is to please and captivate the reader.

The consumption of comics can be joyous, if the work itself satisfies--or confounds--reader expectations. Without a lot of hard, high-focus work, the stories themselves, good, bad or so-so, wouldn't exist for us to snarf down. As Dan Nadel sagely notes in his introductory text to the book Art In Time:

"A worthy story... is always the difficulty of comics."

Thus, mainstream Golden and Silver Age comics about the act of making comics were seldom too playful. It's as if all the hard work of creating comics--the unavoidable writing and drawing, the late-nighters and tense deadline hauls--has made them a sacred cow.

Modern comics have embraced autobiography--from the pioneering efforts of Justin Green, Robert Crumb and Harvey Pekar to modern practitioners such as Joe Matt, Seth, and even Yoshiro Tatsumi. The comic book that has received the most critical praise and attention, Art Spiegelman's Maus, is, in part, an autobiography--which includes scenes of the act of making comics. (Spiegelman's recent MetaMaus takes this duality even further.)

A medium as reflective, and as malleable, as comics begs for a playful attitude--in both creators and consumers. Comics about comics (CaCs) have the potential to unleash an antic side of its creators' psyches. Why, then, were so many earlier comics-on-comics so self-deprecating--and so unrevealing of the true nature of making comics? Is this a reflection of the low status of the comic-book artist?

Take, for example "Cartoonist's Calamity," the nightmarish Bill Everett saga of a cartoonist's world that appeared in Timely-Atlas' Venus #17 (Dec. 1951).

Jimmy Rogers, the harried protagonist of this story, is one stressed-out soul, at once alienated and alienating to others. The pressures of his job as cartoon editor of Beauty magazine (the home base of the Venus universe) have turned him into a hostile, sunken-eyed abuser. (To read this Everett gem, see our earlier posting here.

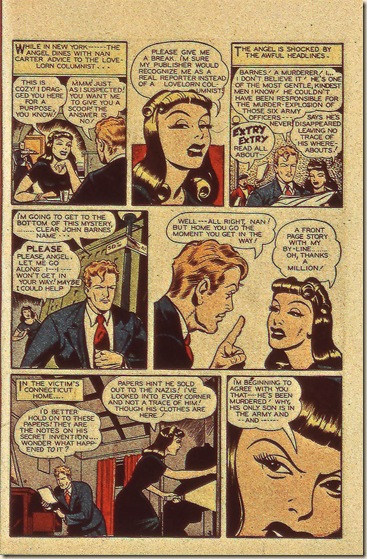

Speaking of Kalamities, there's the klassic E.C. fillip, "Kamen's Kalamity" (Tales From The Crypt #31- Aug/Sept 1952). E. C. published many CaC stories. They are all about the creators, and not their creations. In "Kalamity," William Gaines, Al Feldstein and Kamen, portrayed as a gentle, affable bad joke-loving goofus, appear in an in-jokey story that parodies the tropes of the E. C. horror stories while also catering to them.

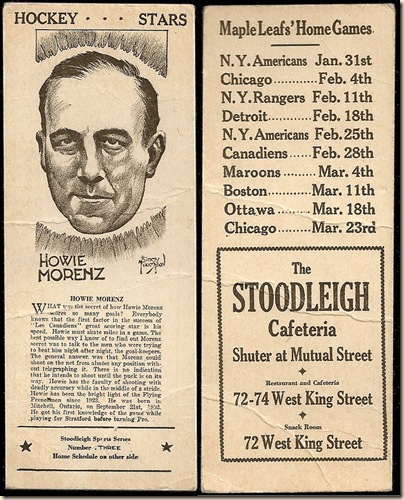

Jack Kamen, as pictured in his E. C. comics profile feature

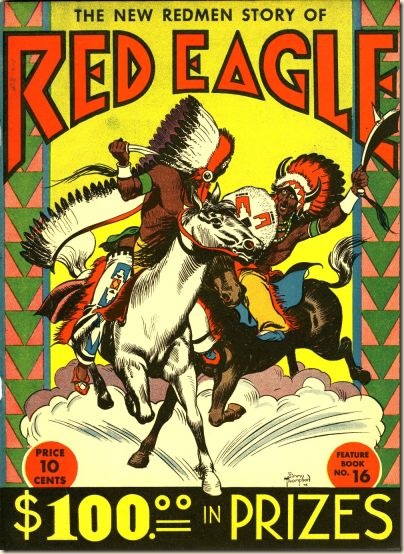

Two excerpts from "Kamen's Kalamity," showing Gaines, Feldstein and artist Kamen

Whimsical though these E. C. CaC stories are, they reveal nothing about the actual process of creating comics. The character sketches of Gaines and Feldstein, as hyperbolic worry-warts in search of a story gimmick, are amusing, but they don't offer a real picture of their work process. As can be seen by Kamen's publicity picture above, the E. C. staff were working stiffs, sleeves rolled up, cigarettes smoldering in a nearby ashtray, and butts numb from hours in front of the drawing board. The E. C. creators lavished remarkable visual--and verbal--detail on their stories. These were not laugh-happy playboys, dashing off comics stories in a festive mode.

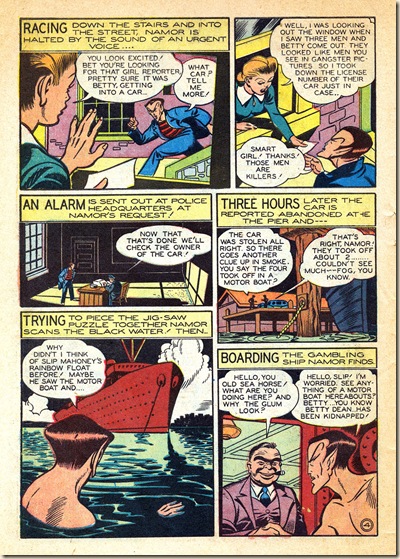

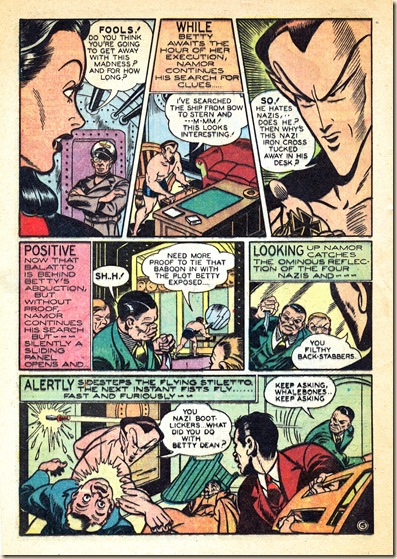

One of the forgotten, longest-running CaC series was Quality Comics' Pen Miller, an Ellery Queen flavored riposte about a crime-solving cartoonist, The feature ran for almost all of the 1940s in National Comics and then Crack Comics. Again, the profession of a cartoonist/comic book creator takes a back seat to something much more glamorous. The talented Klaus Nordling penned Pen.

Curiously Miller's cartoon style looks exactly like Nordling's. To our knowledge, Nordling never actually portrayed himself in his own CaCs. You can read several examples of "Pen Miller" here.

A considerably more autobiographical, and winning treatment of the profession of cartooning occurs in Sheldon Mayer's baby, Scribbly. This feature was even longer-running, starting in the proto-comics of the mid-1930s and lasting into the early 1950s. Like almost all of the early CaC stories, Scribbly is short on the details of the art of creating comics, but it does go a long way towards sharing the sheer love of making comics.

Here's a sequence from the series' early years that shows Mayer's CaC feature was solidly about the adventure of being a cartoonist more than the reality.

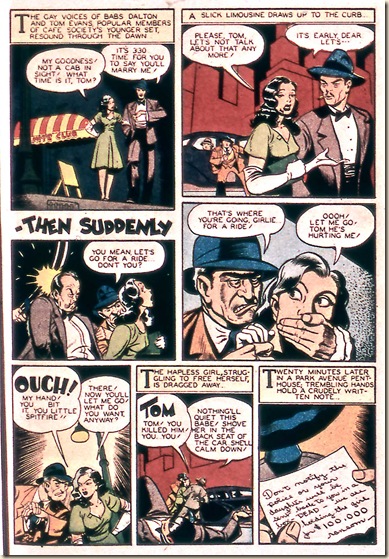

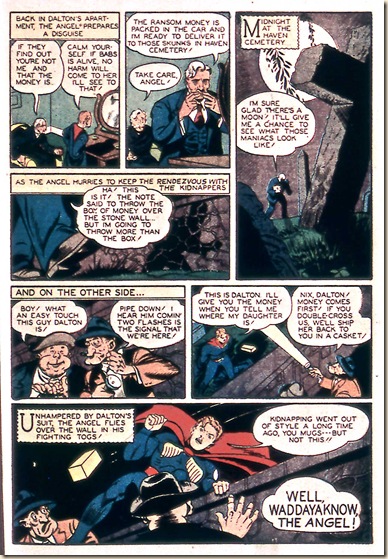

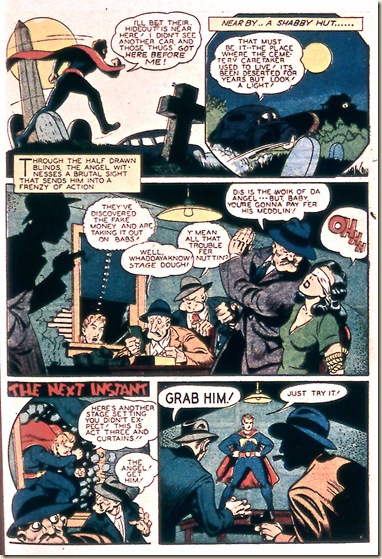

Another comics master who put a version of himself into his stories was Jack Cole. Starting in his earliest stories, he also captured the sheer joy of comics -- as if imagining a super-hero into existence was the sames as making him real.

Sadly, Cole -- like nearly everyone in the early years -- tended to portray himself as a goofus. In an early Plastic Man story, he's a stuttering, small-minded hick:

Cole also created two little-known stories featuring a character called Inkie; a sort of "Out of the Inkwell" cartoon come to life. This was part of a long-running series at Quality, but Cole's stories are standouts. Here's one:

Learn more about Jack Cole's self-referential comics at Paul Tumey's blog.

So far, we've exclusively discussed CaCs about cartoonists and their lives in front of--and away from--the drawing board. There is a variant CaC story, seen less often, that is far more creative, self-aware and revealing. In these story, the characters--not the creators--create the content of the stories themselves, as we observe them at work.

In these stories, the work is not polished professional stuff--it's deliberately crude, raucous and rebellious of the craft of comics. Ironically, these stories give us more of the heart and soul of their creators--which makes their relative scarcity truly regrettable.

Here is the second "Lulus Diry," from 1948:

The use of speech balloons, and occasional sound effects, marks "Lulus Diry" as a type of comics. The feature quickly lost its ramshackle look and feel, but continued through Stanley's tenure on the Little Lulu title. You can read more about "Lulus Diry" here at Frank's blog, Stanley Stories.

Before "Lulus Diry," one of the dream teams of Golden Age comics had pioneered this approach. Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, while at DC Comics in the early 1940s, brought tremendous energy and charm to a comics imprint more known for its bland, polished product. In and of themselves, the Simon-Kirby work for DC expresses the love of creating comics. Their panels burst with energy and attitude, and their pages defy the orderly grids of Superman and Batman.

In one of their last stories for DC, Simon and Kirby directly reference the making of comics, from the flawed hands of their own characters, in a single story that shows a path comic books might have taken, but seldom did until the age of autobiographical comics.

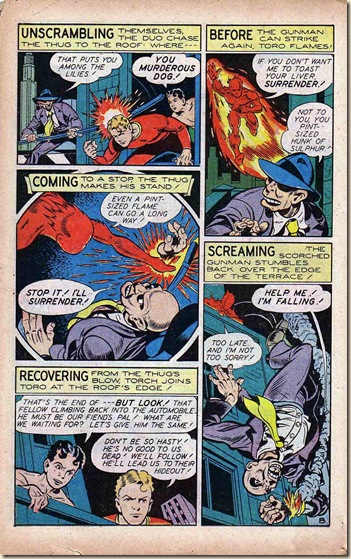

"Cabbages and Comics," from Star-Spangled Comics #29 (Feb. 1944), combines the rowdy, Warner Brothers-like atmosphere of the Simon-Kirby comics world with a berserk attack on the law and order of the comic book field, circa 1944. Joe Simon's inking seems a bit berserk, itself, on the first few pages of the story, but as it continues, we see a prime example of the Simon-Kirby team at the top of their game.

In this story, the kids of the Newsboy Legion decide to create their own, hand-drawn comic book for their neighborhood of Suicide Slum. Talk about a labor of love! Each edition Suicide Slum Comics is individually hand-crafted by the Legion--in a remarkable anticipation of the DYI mini-comix movement that began in the 1970s.

There's nothing remotely like this elsewhere in the history of early comic books. Before we show you the story, please take a moment to savor this highly subversive burst of raw energy...

Each panel is drawn (and signed) by a member of the Newsboy Legion. Like "Lulus Diry," these intentionally primitive drawings reveal something about the consciousness of the characters. For example, the garrulous Gabby can only draw stick figures:

Big Words' frames betray his significant, erudite vocabulary, and a rudimentary understanding of foreshortening--which, in turn, reveals the hand of Jack Kirby, with a sly wink:

Scrapper's take on comics anticipates Gary Panter by four decades:

And now, here is "Cabbages and Comics," including its cover image, for yez readin' enjerment...

"Cabbages and Comics" emerges from a void which immediately sealed itself for several decades. American comic-book creators, prior to the autobiographical pioneers, seemed to assume that their profession was too lowly to portray realistically. Nor were they comfortable enough to approach their trade with such lunacy as Simon and Kirby--who themselves, in the mid-1940s, reached a level of self-confidence (and star status) that few of their peers attained.

This is by no means an exhaustive survey of Comics about Comics. We feel there is much more to be said on this topic. We hope that, by opening up a dialogue on this seldom-discussed byroad of comics, we can encourage others to contribute to a deeper understanding and appreciation of this flexible, playful and reflective art form.

--Paul Tumey and Frank M. Young, 2011

P.S.: Alter Ego #105 features an abridged, full-color version of our premiere Comic Book Attic article. Look, Ma, we're in print! You can buy the paper or digital version of this new issue here.